Today I want to share this beautiful story of a surprise breech homebirth from Patsy Harman, a midwife and author:

In the 1980s I lived the back-to-the-land communal life-style in rural West Virginia and became what used to be called a lay-midwife. This is a Breech Birth story, my 73rd delivery, adapted from my memoir about those years, Arms Wide Open: A Midwife’s Journey. To see more about my other novels and memoirs and my first juvenile book, Lost on Hope Island: The Amazing Tale of the Little Goat Midwives go to www.patriciaharman.com

I Would Do Anything for Love

A surprise homebirth breech

Gripping my worn, brown leather birth bag, I approach the back door of the peeling white farmhouse and knock twice. My stomach churns. I’ve made a home visit to Shawn and Sue Ellen’s hippie farm months ago, but I’ve no idea what kind of scene I’ll find tonight. The stereo blares inside the house and I knock again louder.

A thin man with a long grey beard, who looks like a guitarist from ZZ top, cracks the door. “Yeah?” he asks suspiciously and for a minute I think I’ve got the wrong house.

“I’m Patsy, the midwife. Are Sue Ellen and Shawn here?”

“Well, it’s about time!” The old guy throws the door wide and the kitchen light and the voice of Meat Loaf on a stereo spills out at our feet. “Get on in here. I thought I might have to deliver this baby myself! How you doin’? He sticks out his work-worn dry hand and I shake it. “They’re in the back. I’m their neighbor, Sam Trout.”

At the end of a narrow hall, I hear moaning and there find Sue curled on her side wearing nothing but a red flannel work shirt. I notice a streak of bloody-show on her thigh. Her long blond hair is braided down her back, her face pink and shining with sweat. Shawn, a Vietnam War vet, sits at the bedside wearing a black Grateful Dead T shirt. “Take a sip of water,” he orders. He has a Mohawk haircut and there’s a tattoo of a snake curled around his huge bicep. The young woman takes a cleansing breath, lets out her air and tips her head back as her man holds the cup to her mouth.

“They’re really hard, Patsy. I hope it’s not much longer. I don’t know if I can make it.”

“You’re doing great,” I tell Sue Ellen, opening my bag and pulling out my fetoscope. It takes a minute to find the baby’s heartbeat and I’m surprised when I locate the sound just above the belly button, not down by the public bone, where I’d found it at her prenatal visit yesterday. “Perfect. The baby’s in great shape. Nice regular heart beat.”

Next I pull out a pair of sterile gloves and ask Sue Ellen to roll on her back. Contractions are coming on top of each other, and the young woman doesn’t say much, just breathes and does what I tell her.

With two gloved fingers, I follow the vagina up to the cervix and my eyes widen. Six centimeters already! “Shawn,” I begin to bark orders. “We don’t have much time. Can you help me set up?”

“I got to push!” Sue Ellen groans, grabbing onto the sleeve of my sweatshirt.

“No, too early!” I command. “Do like this.” I puff out my checks like I’m blowing out a candle and then my eyes go round. My fingers are still in the Sue Ellen’s vagina as her cervix goes to seven.

But something’s not right. There’s a fissure down the middle of the baby’s head! I shudder, picturing a deformed child and then pull myself together. Fetal heartbeat high on the abdomen? Soft cleft in the presenting part? It’s not a fracture down the middle of the infant’s soft skull, but the baby’s butt crack I’m feeling!

Now my mind goes into overdrive. I’ve never delivered a breech before, never even seen a breech delivery in a childbirth movie. The books say there are so many things that could go wrong.

“Shawn…hold up. We got trouble.”

Sue Ellen starts to freak. “What? What’s wrong? Is something wrong with my baby!”

“The baby’s fine. No problem there. Good fetal heart beat without deceleration. But he or she is coming out breech… backwards… bottom first. I thought the head was presenting yesterday. I’m sure it was, but it must have flipped.

“The point is, things aren’t normal. I’ve never delivered a breech before and it’s more dangerous. I’d say we have to go to the hospital right now, but the hospital’s an hour away. I’m afraid Sue the baby will come before we can get there and I don’t really want to deliver my first breech in a car.

“It’s your call, Sue Ellen and Shawn; I’ll do whatever you want. We might make it to the hospital. Either way , there are risks.” I touch Mr. Trout on the arm and we step into the darkened hall to let the couple talk. A few minutes later, Shawn calls us back in.

, there are risks.” I touch Mr. Trout on the arm and we step into the darkened hall to let the couple talk. A few minutes later, Shawn calls us back in.

“We want to stay here,” he announces, simply, then goes back to his woman. I pull in my lower lip, not sure if I’m relieved or more terrified.

“I need a moment,” I tell Shawn. “Can you lay everything in my bag on the dresser …and don’t let Sue Ellen push. I’ll be right back.”

Outside in the back yard I find a tree to lean on. I need strength for whatever’s before me. With my arms around a great silver maple and my cheek on the smooth bark, I whisper, Great Spirit, steady these shaking hands. Help get us through this. Protect Sue Ellen and her baby. Be my guide. My whole body is pressed alongside this huge living being and when I feel the tree breathe against me and the leaves rustle above, I’m no longer afraid.

“Miss?” Sam Trout shouts into the dark, his head poking out the kitchen door. “Miss, Patsy. They’re callin’ for you.”

In the bedroom, Shawn is holding Sue Ellen up, by sitting behind her on the bed. She has her legs open and is instinctively bearing down. A tiny butt cheek already shows.

“Sorry,” Shawn says. “I told her not to push, but she says she has to.”

I place my sterile scissors, olive oil, two hemostats, gauze and cord clamp on a clean towel on the edge of the bed then spread open a copy of Varney’s Manual for Midwifery to the chapter on Breech and glove up.

Sometimes a breech baby will poop in your hand, black gummy stuff called meconium, but Sue Ellen’s infant is too refined. “It’s a girl,” I tell the group. “This is the only kind of delivery you can know for sure the gender of the baby before it’s born. No balls or penis!” I find this amusing, but I’m the only one laughing.

Meat Loaf is still singing in the background, “I would do anything for love.” Shawn’s face is white and his Mohawk droops to one side. Sam Trout leans against the doorway, as relaxed, as if he’s observing a Jersey cow give birth in his barn. I glance again at the illustrations in the medical volume.

Every two minutes, Sue Ellen pulls her legs back, grits her teeth and with great courage bears down. Shawn wipes her face with a cool rag and with each push more of the bullet shaped body appears.

“It’s up to you now, Sue Ellen! You’re almost done. I can feel the cord pulsing, so we know the baby’s getting enough oxygen. And she’s got her arms at her side where they belong.” I say all this like I know what I’m doing, but it is only the pictures in Varney’s Midwifery that reassure.

“Towel,” I say to Mr. Trout and, like a surgical nurse, he hands me a clean green striped dishtowel.

Imitating the directions in the text, I wrap the fabric around the baby’s wet hips and lift up. With my other hand, I press my fingertips into the Sue’s lower abdomen, cup the baby’s head through her flesh and keep the fetal skull tipped downward.

“This is it Sue Ellen, everything’s out but the head. Push like you mean it and if you run out of air, grab some more and go down again. Push until I tell you to stop.” The mother pulls back her legs one more time and puts her chin on her chest. Shawn, grim faced, leans over to support her. We all bear down, willing this baby to be born and it occurs to me that, if we needed to, we could lift the whole farmhouse.

Now the infant’s body is out, drooped over my forearm and slowly, gently, the rest of the head delivers, first the nape of the neck, then the ears, and finally, the soft wet black hair. No episiotomy. No tears. I let the whole baby fall into my lap, pink and already crying.

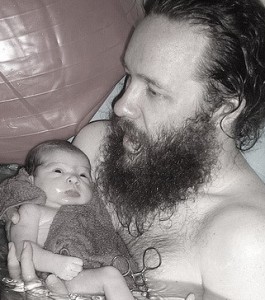

We all cry, even Shawn, the hardened Vietnam vet with the Mohawk and Patsy, the midwife who never cries at a birth.

Bow down. Bow down. And sing the praises of the small, the weak, the miraculous. Outside the bedroom window, the undersides of the new green maple leaves reflect the rising sun. Meatloaf is still singing over and over. “I would do anything for love. I would do anything for love…”